Speaking in tongues: the songs of Van Morrison

Martin Buzacott and Andrew Ford (ABC Books 2005)

Excerpt from Part One

A Soul in Wonder: Themes and Variations

Like Tennyson’s Ulysses, Van Morrison is a part of all that he has met, a storehouse of experience and memory. To listen to Van Morrison singing his songs is to get inside his cluttered mind and follow him on remembered journeys around the East Belfast of his youth, up this street, down that avenue, across the viaducts, beneath the pylons. You’re carrying a window-cleaner’s ladder, on your back a knapsack containing Paris buns, the latest Ray Charles single and a copy of Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums.

The landscape has a familiarity, and yet you feel a sense of wonder. All around you are childhood memories, and they provoke your imagination, inspiring you to the extent that you are constantly searching for a higher meaning and a connection with some perfect silence, most likely to be found in nature or in some ancient past. Frequently disappointed in your quest, and too often encountering shysters and people who distract you or seek to thwart your progress, you soldier on out of a sense of duty and because it’s your job (you are a Protestant and have a work ethic to match). Sometimes when you’re in a good mood you might hanker after a companion who will share the mystical quest with you, and if she’s female, you will walk with her down by the river (or railroad, or avenue), listening together to the wind in the willows, and at the end of the day the two of you might retire inside for a little bit of conversation, play some old blues, soul or jazz records, and then finish it off with that old backstreet jellyroll.

These repeated patterns of creative behaviour —the childhood reminiscences, the spiritual searching, the nature-worship, the homages to musical idols, the themes of innocence, experience and complaint—are everywhere in Morrison’s work. They are the building blocks from which the he constructs his songs and imaginative landscapes [. . .]. And in one of the most consistent careers in popular music, most of [these themes] were there right from the very beginning.

In autumn 1968 when he recorded his first proper solo album, Astral Weeks, Van Morrison had just turned 23. The degree of retrospection embodied in it is, then, surprising. Most 23 year-old men do not sing about their childhood. Most 23 year-old men do not even sing about the past: they sing about their girlfriends or their car, and the songs are in the present tense or in an ideal, chimerical future. But there, on Astral Weeks, on what are still regarded as some of his finest songs—‘Cyprus Avenue, ‘Madame George’, and the album’s title track—Morrison is already busy reminiscing.

Although it was surely never intended, Astral Weeks now seems like a manifesto, a statement of intent: this is the kind of artist I am, and this is what I will remain. In the first verse of the first song—‘Astral Weeks’ itself—we hear about venturing in ‘the slipstream’ which is ‘between the viaducts of your dream’ and we encounter his desire to be ‘born again’. These are words, images and themes that Morrison revisits to this day, and from the start some of these were more transparent in their meaning than others. The viaduct, for instance, is a tangible symbol of his childhood in East Belfast. Singing ‘Summertime in England’ at a New York concert in 1990, he intones the word over and over: ‘Viaduct, viaduct, viaduct, viaduct’. It becomes an incantation of an almost spiritual nature, similar to his whispered pleading at the end of Into the Music (1978) to meet him ‘down by the pylons’. One imagines these viaducts and pylons as symbols of Morrison’s childhood and early teenage years: tadpoles in jam-jars, illicit cigarettes, R&B records and the first, furtive fumblings of adolescent sex.

From the very start of his solo singing career, it was these songs in celebration of an idyllic youth that were least close to jazz, blues, soul or gospel, the popular music forms in which Morrison had been steeped as a child. Most significantly for 1968, the songs on Astral Weeks could hardly have been considered rock and roll ‘in any ordinary or hyphenated sense’, as Greil Marcus wrote at the time. Harmonically, these songs and all the childhood songs that followed tend to have a modal simplicity whose roots are in Celtic folksong . . .

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Australians all let us read Joyce ..for we are young and free

About Me

- FXH

- My Work: Special In-Vestments Advisor and Emergency Spiritual Guru to Jesuits Gaming and Adult Services Australia. Caulfield Holden, Xavier Herbert, St Francis Xavier

Labels

Blog Archive

-

▼

2004

(83)

-

▼

August

(19)

- oz politics easy reference guide

- elvis quotient - on watch

- abc radio bows to blog pressure

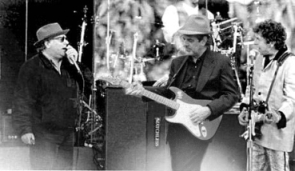

- the trinity, the holy ghost, van

- might come in handy one day

- ruby ann boxcar

- like a circle in a spiral, like a wheel within a w...

- bob + willie + western swing = bliss

- porn - moral panic

- busy week already

- youthful exuberance - my arse

- farting as a defence against unspeakable dread

- same till different hands

- song for richard butler & peter hollingsworth

- doctors and torture - abu ghraib - guantanamo bay

- sweet f (t) a

- i pledge allegiance to the flag .....

- the family pharma

- flip flop and fly

-

▼

August

(19)